Salgyeol by HeinKuhn OH

with essay by Daniel Rubinstein

Salgyeol by HeinKuhn OH with essay by Daniel Rubinstein

Portraits by HeinKuhn OH

with essay by Daniel RubinsteinThis story originally appeared in

SOL 2. Kyoyuk issue 2019

The Body as a Data Set

On the work of HeinKuhn OH for SOL MAGAZINE

What is the reason for the enduring fascination of the photographic image?

Stop taking them, looking at and sharing them and ask yourself how you are experiencing photographs. The traditional view is that the two-dimensional world of the photograph is a projection of the three-dimensional world. Guided by the intuition that photographs lead us back to people, events and situations, we continue looking at our screens without ever considering what is it that we are looking at.

There was a time when photography was relied upon to provide evidence, to record and to document the world, but in the age of big data, biometric identification systems and mass surveillance of all electronic communication, photographic record-keeping became obsolete. These days we collect data rather than snapshots, even if some of the data still comes in familiar forms.

What makes the task of understanding present-day photography especially tricky is the ostensible transparency of the picture, the lingering impression that we are simply looking at someone doing something, or at a cat or a cactus. When in fact, every photograph is at one and the same time a measurable representation of a specific time-space (this body in that location) and an immeasurable one (data spread throughout the networks) that cannot be located in any precise time-space coordinates.

Because the photograph is both a still visual image and a perpetual flow of data it offers a glimpse into new forms of consciousness that happen when we outsource parts of ourselves to the smartphone, the cloud and the server that operate in the interests of capital and profit. The big difference between Capitalism in the 20th century and Capitalism in the 21st is that the former used industrial machines to exploit the labor of the workers while the later uses smartphones and social media to exploit the life-experience of the users.

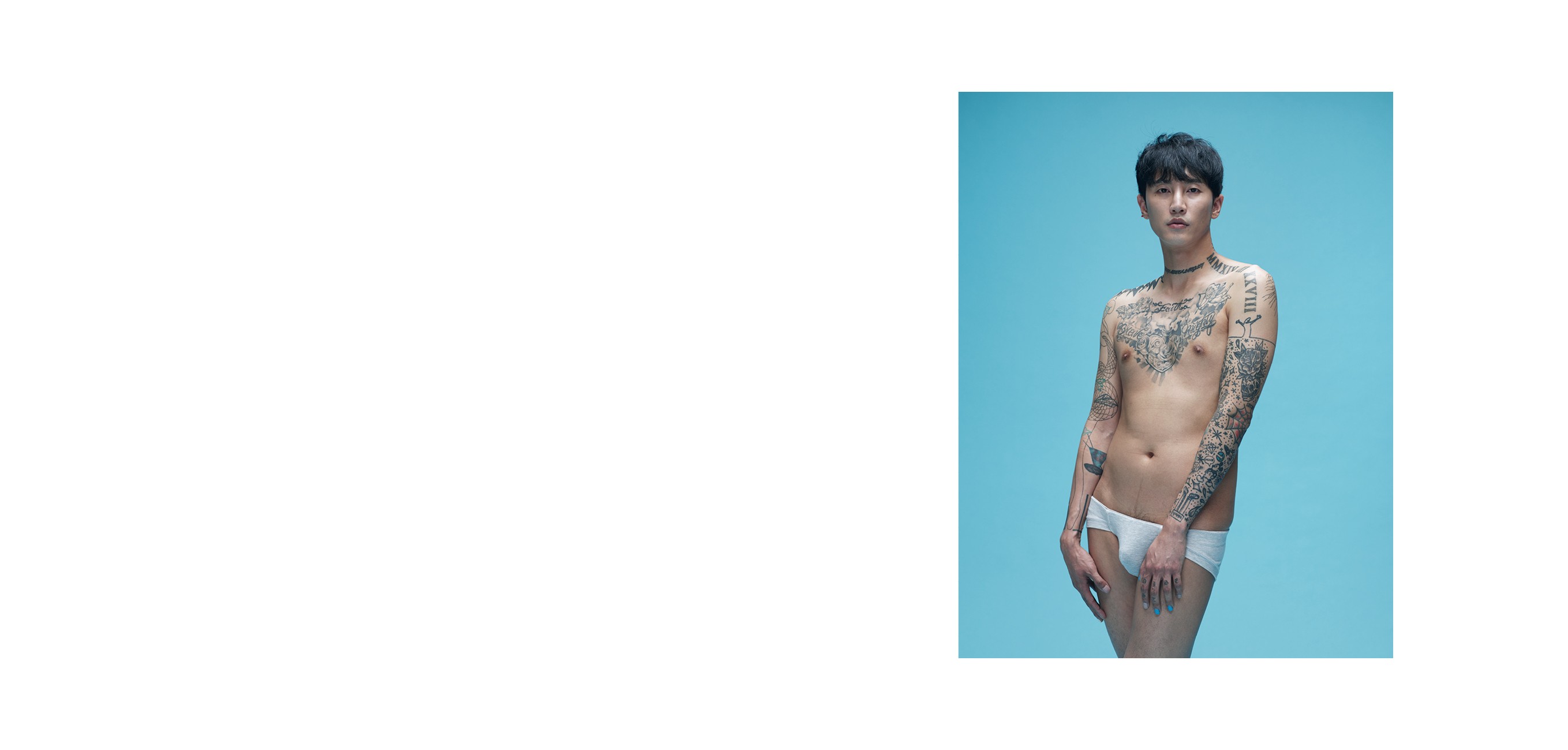

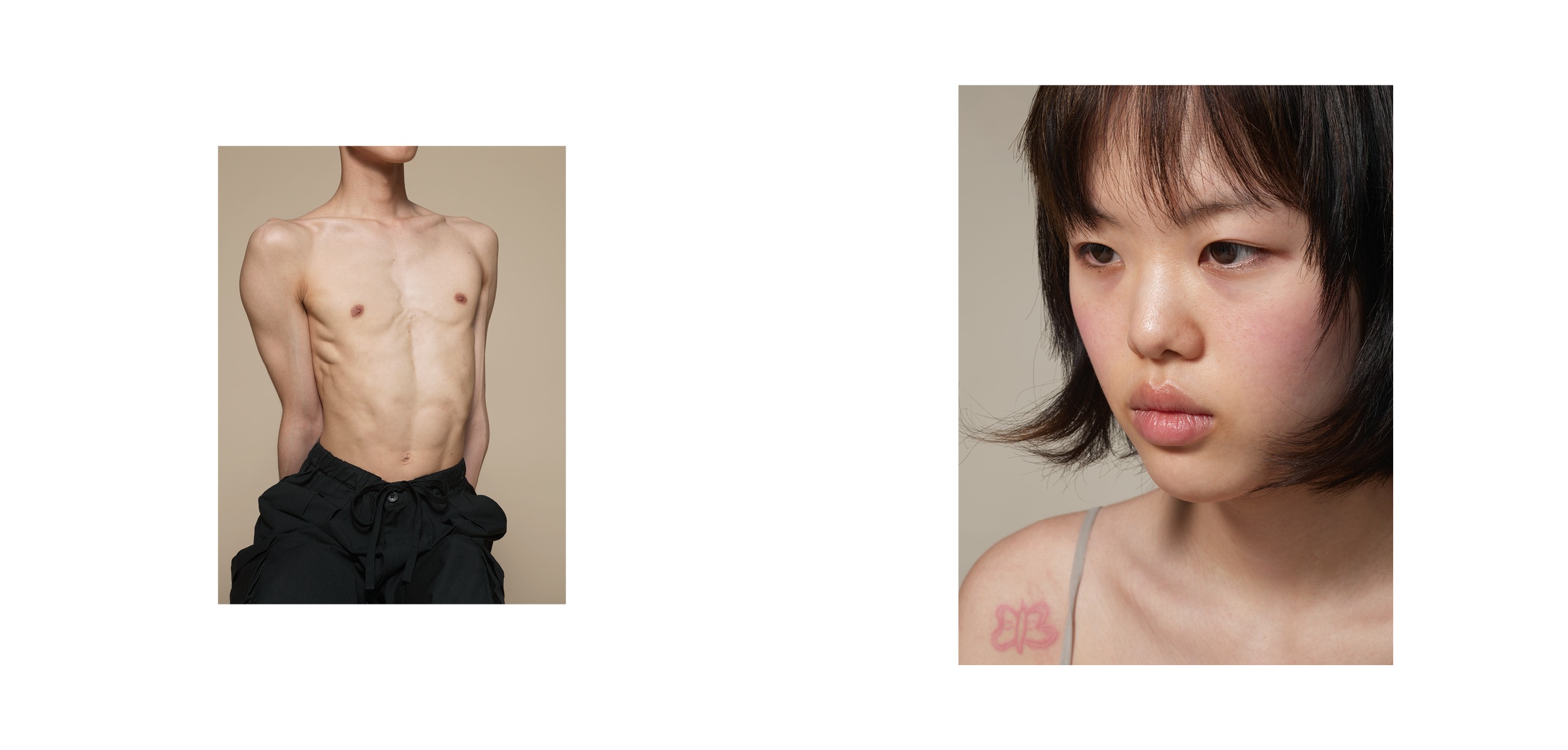

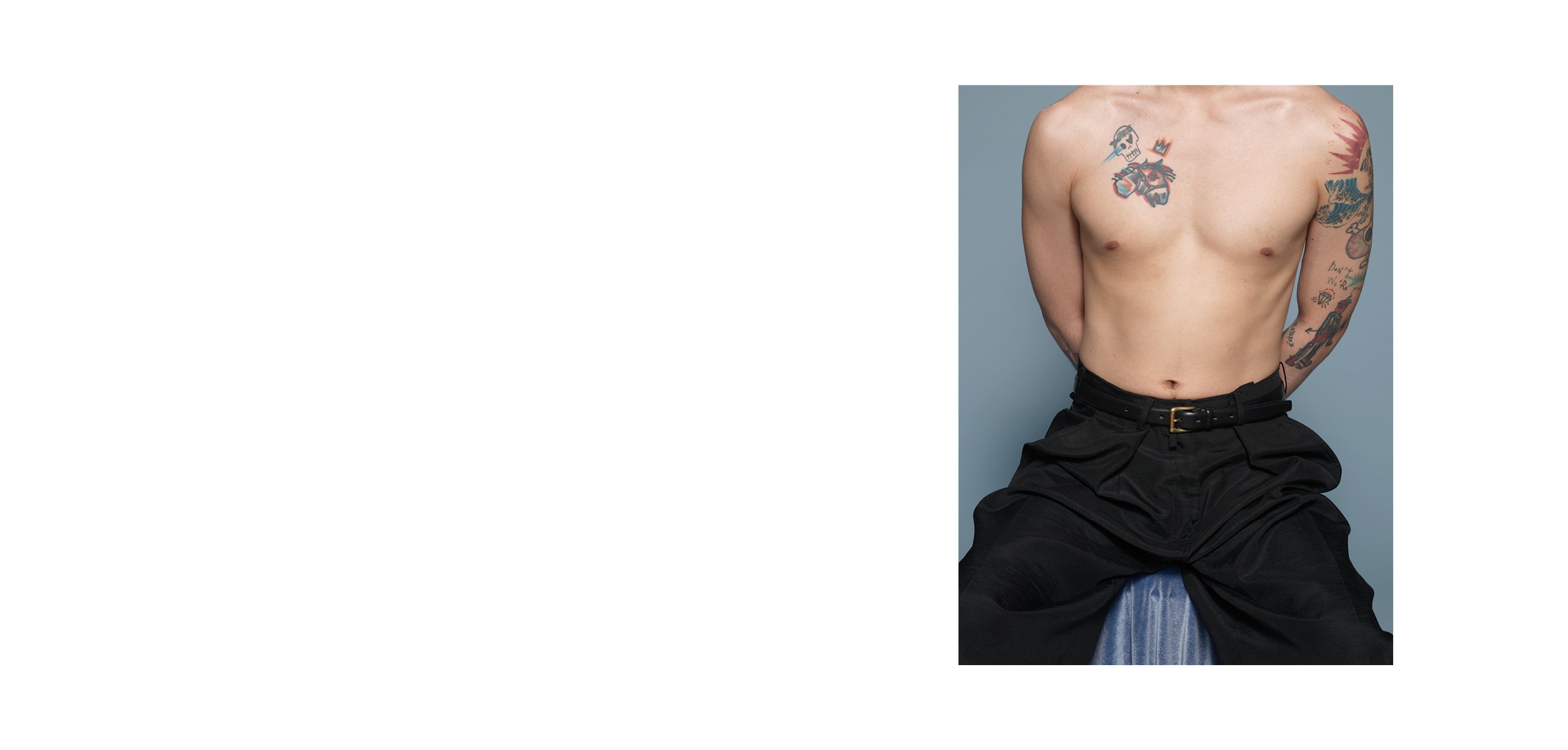

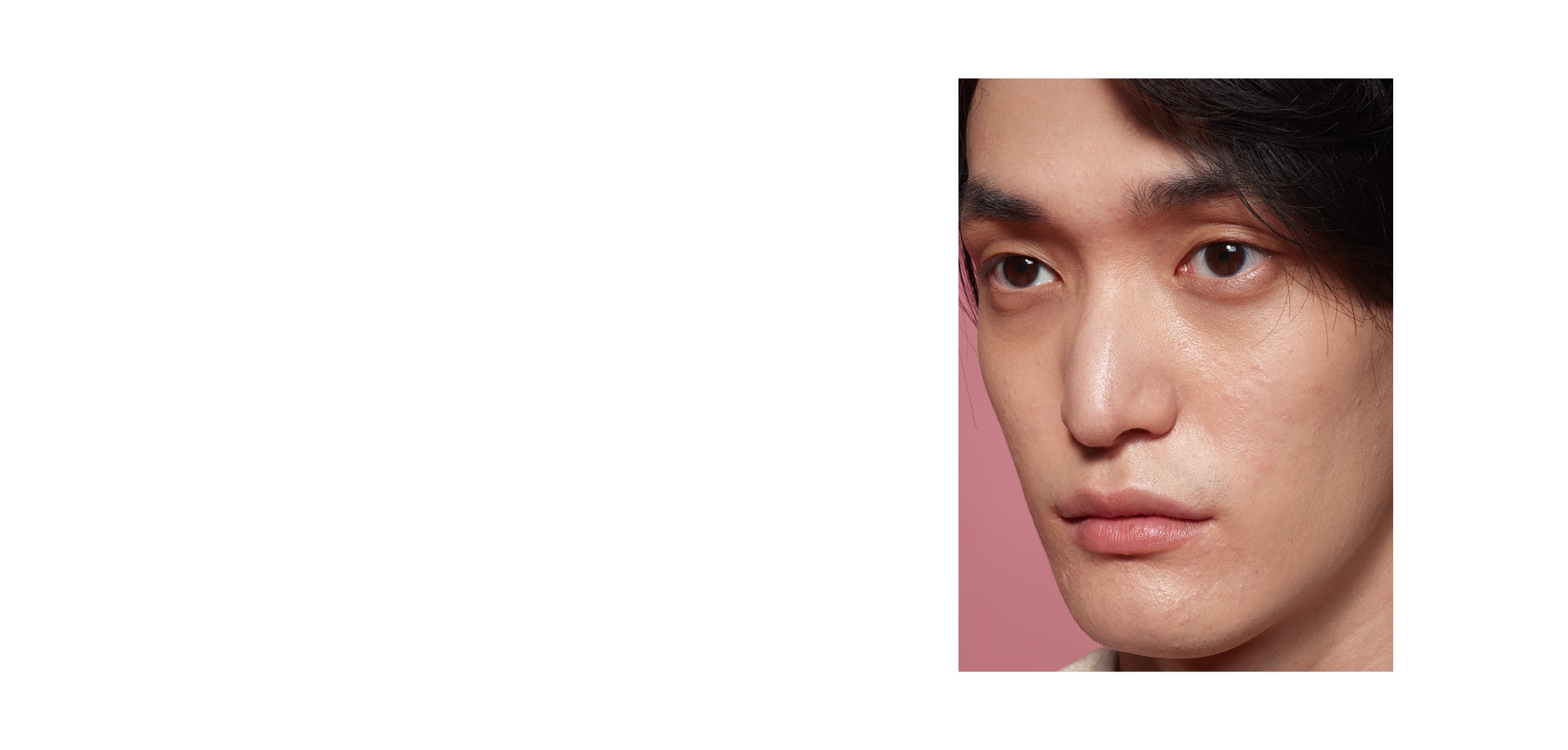

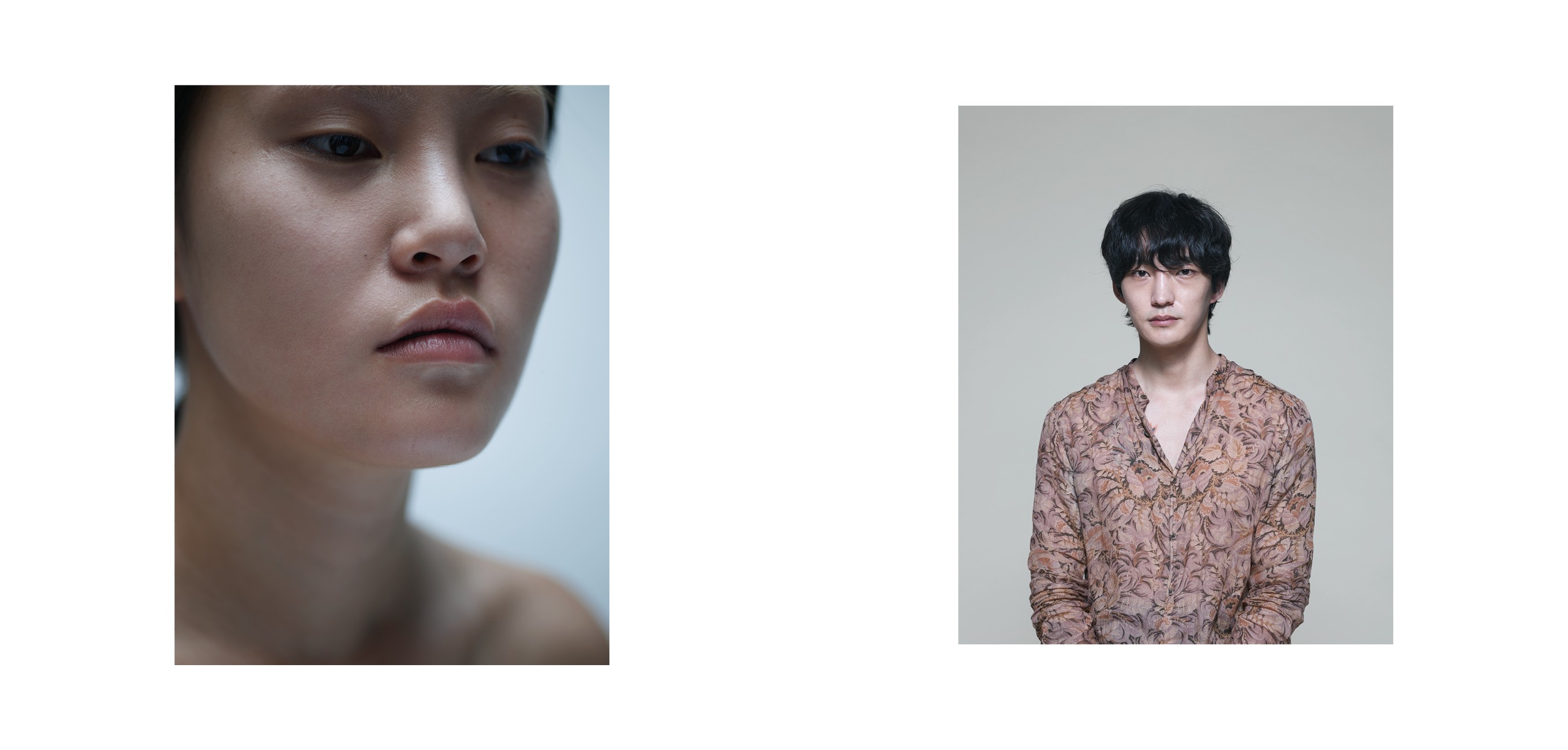

HeinKuhn OH's photographs propose a mediation between the European Enlightenment idea of individualistic subjectivity (free, autonomous, universal, and rational) and the bio-political colonial stereotyping by updating it for the realities of the ‘digital natives’ – those of us who have not known a world before the Internet. When we look at his images, we can see what existence that is shaped by social media looks like. This Human_2.0 is in stark contrast to the Western individual as an agent of moral choices and logical reasoning. A photograph of a person is not a portrait, even if it bears superficial similarities to the tradition of portraiture in painting. The subjects of these images seem to be rejected by the very social and cultural codes with which they are trying to assimilate. The photograph here is conditioned not by what is visible in it, but by what cannot be represented; by the incomputable algorithms that compile and combine data.

The indeterminate qualities of the bodies (androgyny) correspond to the random data from which these bodies were selected. The bodies in these images are isolated like specimens in a petri dish, but they are imperceptibly linked to algorithms which, like these bodies are able to adapt and respond unpredictably to external stimuli – to the presence of the photographer and of us, the viewers. Disappointingly, most of them are young and beautiful; one can only wonder what this project would look like if it allowed the inclusion of less conventionally attractive human forms.

The models are often naked or undressed, but this is not nudity in the traditional sense of erotic display. The boundary between public and private is abolished. The naked body has to be decoded not according to the logic of desire but according to the principles of augmented reality in which everything is possible and nothing is real. Computation becomes indistinguishable from life. It does not make sense anymore to draw a dividing line between an image and life because reality is neither in the image nor is it in life, but in the links between them.

These images are instructive because they demonstrate what happens when human bodies are extended with computational networks. When computation is crossed with bio-physical variables such as gender, sex, age, skin, hair, the raw material for algorithmic processing is not alfa-numeric data but the human soul. What cannot be repeated often enough is that the adversarial neural networks of Instagram are not searching for images that are similar to the ones you already liked, rather they track your behaviour online and offline to determine what are your tastes and preferences and base their suggestions on knowing you better that you know yourself. For Instagram, Facebook and Google the image is not a portrait or a selfie, it is only a bait to provoke a behavior that can be matched against your past behaviors and the behaviors of other users to condition and modify your future actions in ways that satisfy the needs of those companies.

In the 20th century photographs were often considered as exact replicas of real things, the more realistic a picture was the more it was said to be true to life, but in the 21st century photography’s truth is in the act of producing the unimaginable: a peculiar blend of computation and Erotic desire that eliminates the distinction between reality, thought and imagination.

To answer the question asked at the beginning of this essay, the photograph is fascinating not because it shows us what the other looks like, but because it shows us how we see ourselves.

What makes the task of understanding present-day photography especially tricky is the ostensible transparency of the picture, the lingering impression that we are simply looking at someone doing something, or at a cat or a cactus. When in fact, every photograph is at one and the same time a measurable representation of a specific time-space (this body in that location) and an immeasurable one (data spread throughout the networks) that cannot be located in any precise time-space coordinates.

Because the photograph is both a still visual image and a perpetual flow of data it offers a glimpse into new forms of consciousness that happen when we outsource parts of ourselves to the smartphone, the cloud and the server that operate in the interests of capital and profit. The big difference between Capitalism in the 20th century and Capitalism in the 21st is that the former used industrial machines to exploit the labor of the workers while the later uses smartphones and social media to exploit the life-experience of the users.

HeinKuhn OH's photographs propose a mediation between the European Enlightenment idea of individualistic subjectivity (free, autonomous, universal, and rational) and the bio-political colonial stereotyping by updating it for the realities of the ‘digital natives’ – those of us who have not known a world before the Internet. When we look at his images, we can see what existence that is shaped by social media looks like. This Human_2.0 is in stark contrast to the Western individual as an agent of moral choices and logical reasoning. A photograph of a person is not a portrait, even if it bears superficial similarities to the tradition of portraiture in painting. The subjects of these images seem to be rejected by the very social and cultural codes with which they are trying to assimilate. The photograph here is conditioned not by what is visible in it, but by what cannot be represented; by the incomputable algorithms that compile and combine data.

The indeterminate qualities of the bodies (androgyny) correspond to the random data from which these bodies were selected. The bodies in these images are isolated like specimens in a petri dish, but they are imperceptibly linked to algorithms which, like these bodies are able to adapt and respond unpredictably to external stimuli – to the presence of the photographer and of us, the viewers. Disappointingly, most of them are young and beautiful; one can only wonder what this project would look like if it allowed the inclusion of less conventionally attractive human forms.

The models are often naked or undressed, but this is not nudity in the traditional sense of erotic display. The boundary between public and private is abolished. The naked body has to be decoded not according to the logic of desire but according to the principles of augmented reality in which everything is possible and nothing is real. Computation becomes indistinguishable from life. It does not make sense anymore to draw a dividing line between an image and life because reality is neither in the image nor is it in life, but in the links between them.

These images are instructive because they demonstrate what happens when human bodies are extended with computational networks. When computation is crossed with bio-physical variables such as gender, sex, age, skin, hair, the raw material for algorithmic processing is not alfa-numeric data but the human soul. What cannot be repeated often enough is that the adversarial neural networks of Instagram are not searching for images that are similar to the ones you already liked, rather they track your behaviour online and offline to determine what are your tastes and preferences and base their suggestions on knowing you better that you know yourself. For Instagram, Facebook and Google the image is not a portrait or a selfie, it is only a bait to provoke a behavior that can be matched against your past behaviors and the behaviors of other users to condition and modify your future actions in ways that satisfy the needs of those companies.

In the 20th century photographs were often considered as exact replicas of real things, the more realistic a picture was the more it was said to be true to life, but in the 21st century photography’s truth is in the act of producing the unimaginable: a peculiar blend of computation and Erotic desire that eliminates the distinction between reality, thought and imagination.

To answer the question asked at the beginning of this essay, the photograph is fascinating not because it shows us what the other looks like, but because it shows us how we see ourselves.